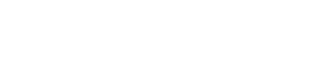

Scientific Research1. What are relativistic heavy-ion collisions?Relativistic heavy-ion collisions accelerate heavy nuclei—such as gold (Au) or lead (Pb)—to nearly the speed of light and let them collide. Unlike a simple “two balls collide” picture, the energy is compressed into an extremely tiny space-time volume, creating a short-lived fireball with temperatures on the order of trillions of degrees. Under such extreme conditions, quarks and gluons are no longer confined inside individual hadrons (protons, neutrons, mesons). Instead, they form a collective state known as the Quark–Gluon Plasma (QGP).

Figure 1: Schematic space–time evolution of relativistic heavy-ion collisions (Extra) What do we actually “see” in the detector?We do not observe the QGP directly. Detectors record the particles that emerge after the medium cools and hadronizes. We measure momenta, energies, flight times, decay products, and correlations, and then infer properties of the earlier hot medium using well-defined observables—yields, spectra, flow anisotropies, and multi-particle correlations. This is similar to atmospheric science: we do not track individual air molecules to measure weather; instead, we infer the state of the atmosphere from observables. In heavy-ion physics, dileptons, quarkonia, and photon-induced processes (UPC) play the role of especially powerful “thermometers” and “diagnostics.”

2. Direction I: QGP properties using dileptons and quarkoniaA central strategy in QGP studies is to choose suitable probes. We focus on two electromagnetic-related probes: dileptons and quarkonia. Their shared advantage is that the final state contains electrons or muons, which undergo negligible final-state strong interactions. This makes them comparatively “clean messengers” of the medium. · Dileptons (e⁺e⁻ / μ⁺μ⁻): They act as electromagnetic messengers. By measuring invariant-mass spectra, transverse-momentum distributions, and correlations with event geometry, we can access thermal radiation and space-time evolution information. · Quarkonia (J/ψ, Υ, …): Bound states of heavy quark–antiquark pairs are highly sensitive to medium temperature and color screening. Different binding energies imply different survival probabilities in the QGP, and regeneration effects may also play a role—both require precise experimental constraints. In practice, an analysis often follows a robust workflow: (i) build signal candidates (e⁺e⁻ or μ⁺μ⁻ pairs), (ii) estimate backgrounds using like-sign pairs, event mixing, or sidebands, (iii) extract signals with fits or template decompositions, (iv) evaluate systematic uncertainties (selection criteria, efficiencies, background models, fit ranges), and finally (v) compare to theory and Monte Carlo simulations, as well as to results across energies and collision systems.

Figure 2: Illustration of the quark–gluon plasma (QGP) (More concrete) What can a student actually do first?· Reproduce a standard analysis chain: data quality → event selection → tracking/PID → candidate building → background estimation → signal fitting. · Make and interpret key distributions: invariant-mass spectra, pT spectra, or yield trends versus centrality (collision geometry). · Use simplified models to build intuition (e.g., how thermal radiation shapes spectra, or how quarkonium survival changes with temperature). · Learn “systematics thinking”: vary selection cuts/background models/fit ranges and build an uncertainty budget. These steps may feel “engineering-like,” but they are exactly how reliable physics results are produced within large collaborations: solid validation and systematic control turn a measurement into a robust physics conclusion.

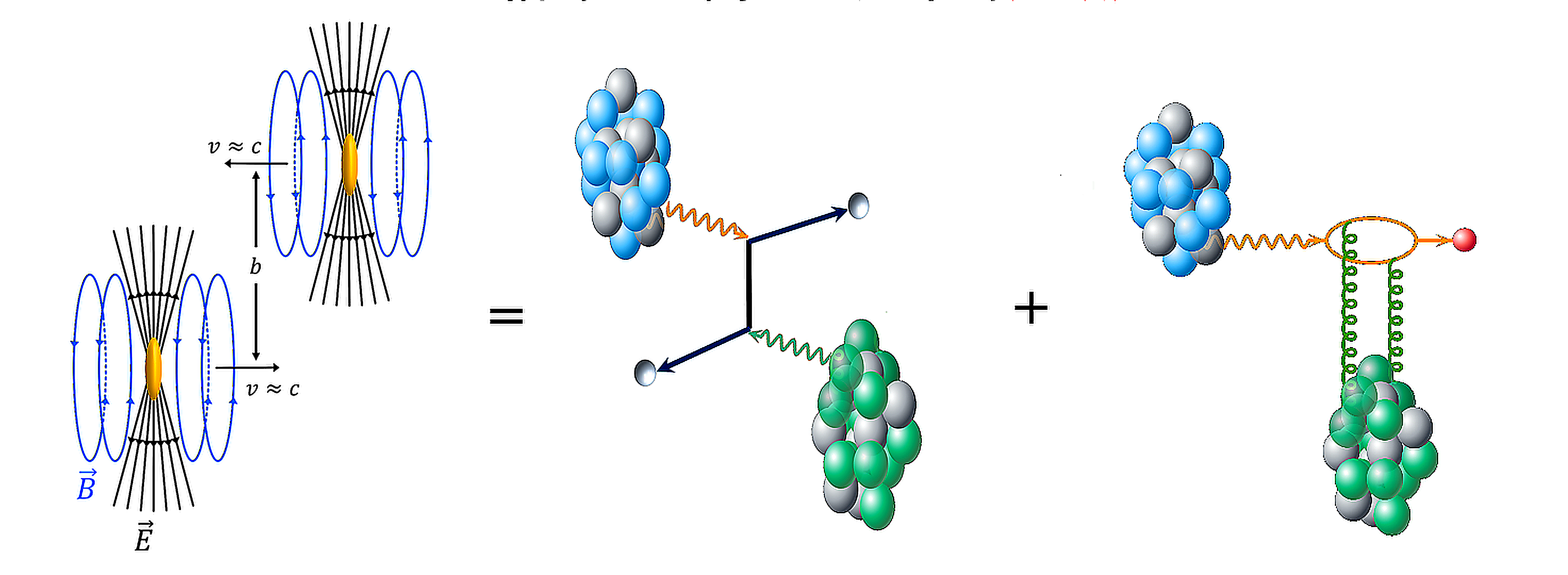

3. Direction II: Ultra-peripheral collisions (UPC) and photoproductionWhen two heavy ions pass by each other with a large impact parameter (so the nuclei do not physically overlap), strong-interaction collisions are suppressed. However, fast-moving charged ions generate extremely strong electromagnetic fields. In an equivalent-photon picture, these fields behave like intense beams of quasi-real photons. This enables studies of γA (photon–nucleus) and γγ (photon–photon) processes—effectively doing “photon physics” with a heavy-ion collider. Why UPC is especially attractive: · The photon flux is enhanced for heavy ions (roughly scaling with Z²), creating an exceptionally bright photon source. · Photon polarization and collision geometry can imprint themselves on angular distributions, enabling sensitive tests of interference and polarization effects. · Neutron tagging with forward detectors (e.g., ZDC) can classify event categories and help control backgrounds and systematics. Typical final states of interest include vector-meson photoproduction (e.g., ρ, J/ψ, Υ), dilepton production, and other electromagnetic processes. Combining perspectives from RHIC (STAR) and the LHC (CMS) supports cross-energy comparisons and deeper understanding of photon–nucleus interactions and nuclear structure.

Figure 3: Schematic of interactions in ultra-peripheral collisions (UPC) (Quick intuition) How to distinguish γA and γγ?A compact way to remember the difference: γγ is “two photons collide” to produce charged pairs or resonances, while γA is “a photon hits a nucleus” and the outcome is sensitive to nuclear structure. Experimentally, the two are separated and cross-checked using final-state topology, neutron-tag categories, and selection strategies. Common student-level tasks in UPC include: understanding triggers and selections, building neutron-tag categories (0n0n/0nXn/XnXn, etc.), studying angular distributions and polarization-related variables, and comparing data to generators or analytic models.

One-minute glossary

|

|